Attacking the Android kernel using the Qualcomm TrustZone

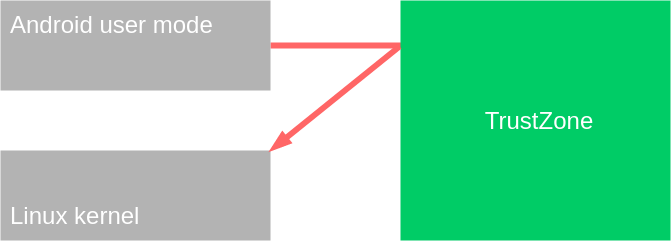

In this post I describe a somewhat unique Android kernel exploit, which utilizes the TrustZone in order to compromise the kernel.

CVE-2021-1961 is a vulnerability I discovered in the communication protocol of Qualcomm’s TrustZone (QSEE). It allows you to corrupt memory management data in the protocol, which I exploited into instructing the TrustZone to modify the Android kernel memory, thus achieving arbitrary read/write primitives over physical memory addresses. I turned this powerful primitive into a reliable exploit that works out of the box without the need to be adapted per device/version.

Exploit TL;DR

In case you don’t feel like going through the full exploit write-up (or maybe read this post already and want to remember what’s in here? ;) here’s a quick summary of both the vulnerability and the exploit. You can also jump to my conclusions, where I discuss this exploit in relation to other Android kernel exploitation/mitigation techniques.

- The QSEE communication protocol allows Android user mode programs to communicate with trustlets. Since this protocol includes shared memory (over ION buffers), a mechanism is in place to make sure trustlets cannot access Android memory other than what was shared.

- The protocol interleaves input data and pointers to shared memory, allowing the user to specify offsets into the input buffer where shared memory addresses should be written to.

- The bug is that there was no check to make sure the addresses don’t overlap each other. By overlapping addresses I could corrupt them, whitelisting other parts of memory, making them accessible to the trustlet.

- To exploit this I used the fact that in some cases not only the shared memory address is written to the input buffer, but also the size, so by overlapping addresses I could also control the size. Then by overlapping addresses of ION buffers that follow certain rules (from different ION heaps) I managed to craft a single whitelist entry to make the whole Android kernel memory accessible to the trustlet.

- Reversing the widevine trustlet, I found functionality that allows encrypting/decrypting shared memory with the same symmetrical key. I used this functionality to encrypt and then decrypt the same data, essentially giving me the ability to copy data from one place to another. Since I made the trustlet accessible to all kernel memory, this gave me arbitrary read/write primitives. Also since the trustlets operate on physical addresses, this is a physical memory arbitrary read + write.

- This was already enough to fully compromise the kernel, but I wanted to make the exploit work out of the box on different devices and versions. I used my arbitrary read to scan the kernel memory for kallsyms and then parse it. This way I was able to figure out where the symbols I want to modify are, without needing offsets for each version.

Preface

Before going into the blog post, I should note that this is not a full root vulnerability, as you do need access to the

/dev/qseecomkernel module, which is not accessible from theuntrusted_appSELinux context. Still, it achieves full reliability and does not need adaptation per device/version, which I think is interesting, especially in relation to other Android kernel exploitation/mitigation techniques.

(Also, I have in the past exploited a vulnerability to get access to/dev/qseecomfromuntrusted_app, so in theory these two exploits could have been chained together)

The Qualcomm TrustZone

The Arm TrustZone is a TEE which allows running a secure OS (Secure World) along the normal OS (Normal World). In Android, an example of one common use for this is cryptography, where the Secure World would be the only one with access to a certain key, and Android could only ask it to perform cryptography operations with it. In Qualcomm devices, the Secure World is called QSEE - Qualcomm Secure Execution Environment1.

Looking into public research around the TrustZone in Android, I found that research into QSEE is a bit rare (especially relative to Qualcomm’s market share), with most research being about Samsung’s TrustZone implementation for Exynos devices. By far the most thorough research into QSEE has been done by Gal Beniamini in his set of blog posts, but the last one has been published in 2016; QSEE has changed since then. With QSEE being closed source, this meant I had to do quite a bit of reversing to figure out some of the stuff here.

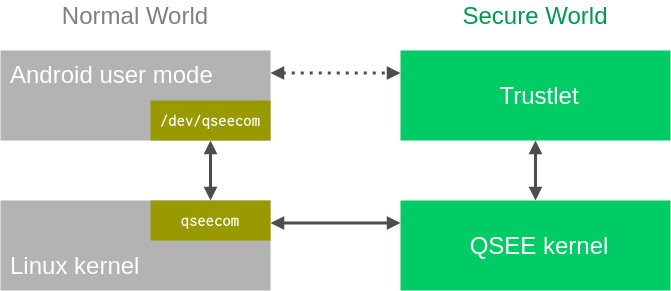

The bulk of communication between Android and QSEE is done between Android user mode programs and QSEE user mode programs, which are known as trustlets. In order to send a command to a trustlet, an Android user mode program will call an ioctl of the qseecom kernel module (/dev/qseecom), which will then send it to the QSEE kernel, which will in turn send it to the relevant trustlet. The response will go through the same components in reverse order.

QSEE Memory Access Model

The first thing that should be noted is that the whole of QSEE, including the kernel and the trustlets, operate in physical memory addresses, not virtual addresses2.

Part of the TrustZone technology allows certain regions of physical memory to be carved out as “secure”, meaning that only the Secure World can access them. This means that there are certain regions even the Linux kernel can’t access.

On the QSEE side, the QSEE kernel is accessible to everything, including the Normal World memory. The QSEE kernel does limit the trustlets, so by default each trustlet can only access a small chunk of secure memory which is its own.

However, in order to allow Android user mode programs to communicate with trustlets efficiently, there is a way for them to share memory.

Normal World <-> Secure World

All data of the commands between Android user mode and the trustlets is passed over shared memory. On the Android side, this shared memory comes from the ION allocator.

The ION allocator allows user mode programs to allocate memory used for DMA (direct memory access) from different ION heaps. From user mode’s perspective, it gets an ION file descriptor which it can then mmap to access the underlying memory. For communicating with trustlets, a user mode program can allocate ION buffers from a dedicated ION heap called qsecom3. This heap guarantees all allocated memory to be contiguous in physical memory, in order to help the trustlet use it.

This is how the basic method of sending commands works:4

- An Android user mode program allocates an ION buffer from the

qsecomheap. - The user mode program

mmaps it and writes the input data to it. -

The user mode program sends an

ioctlto qseecom ofQSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_CMD_REQ. Thisioctlcontains the location of the input data on the ION buffer, and where the output should be written to. Fromqseecom.h:/* * struct qseecom_send_cmd_req - for send command ioctl request * @cmd_req_len - command buffer length * @cmd_req_buf - command buffer * @resp_len - response buffer length * @resp_buf - response buffer */ struct qseecom_send_cmd_req { void *cmd_req_buf; /* in */ unsigned int cmd_req_len; /* in */ void *resp_buf; /* in/out */ unsigned int resp_len; /* in/out */ }; - qseecom sends the physical addresses of the input and output buffers to the QSEE kernel.

- The QSEE kernel gives the relevant trustlet access to the input and output buffers, and then gives the trustlet their (physical) addresses.

- The trustlet can now read from the input buffer and write its output to the output buffer.

- A notification that the request is complete is sent back through the same components in reverse (trustlet -> QSEE kernel -> qseecom -> Android user mode program).

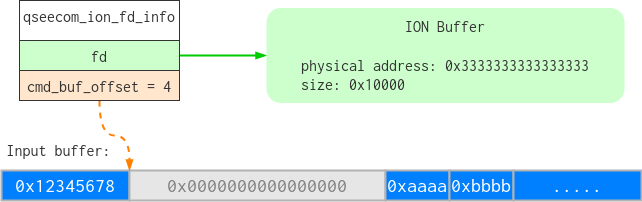

Communicating with pointers

This protocol is not always enough. Some trustlets need to read/write to memory that comes from other ION heaps. To solve this, a command that needs a trustlet to access another ION buffer would have a pointer to that ION buffer inside the input buffer.

However, to do this, there are two issues that need to be solved:

- The Android user mode can’t simply write the physical addresses of other ION buffers to the input buffer. First because it doesn’t know them, and second because letting user mode control what physical addresses are used would be a security issue.

- The QSEE kernel would have to give the trustlet access to the ION buffers that the input buffer points to.

The way that Qualcomm chose to solve this is by killing two birds with one stone. The method is still like the one described above, but with a few additions:

-

Instead of

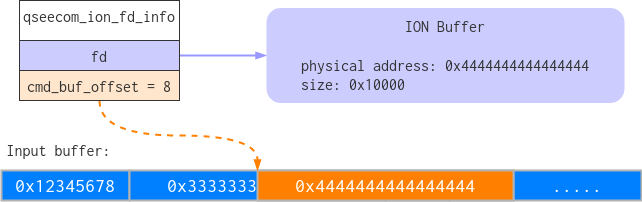

QSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_CMD_REQ, theioctlused isQSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_MODFD_CMD_64_REQ. This one contains the same data of the input/output buffers, but also has up to 4 ION file descriptors, each one with an offset into the input buffer. Fromqseecom.h:/* * struct qseecom_ion_fd_info - ion fd handle data information * @fd - ion handle to some memory allocated in user space * @cmd_buf_offset - command buffer offset */ struct qseecom_ion_fd_info { int32_t fd; uint32_t cmd_buf_offset; }; /* * struct qseecom_send_modfd_cmd_req - for send command ioctl request * @cmd_req_len - command buffer length * @cmd_req_buf - command buffer * @resp_len - response buffer length * @resp_buf - response buffer * @ifd_data_fd - ion handle to memory allocated in user space * @cmd_buf_offset - command buffer offset */ struct qseecom_send_modfd_cmd_req { void *cmd_req_buf; /* in */ unsigned int cmd_req_len; /* in */ void *resp_buf; /* in/out */ unsigned int resp_len; /* in/out */ struct qseecom_ion_fd_info ifd_data[MAX_ION_FD]; }; -

Upon receiving the

ioctl,qseecomwrites the physical address of each ION buffer supplied inifd_datainto the input buffer, at the specified offset. From__qseecom_update_cmd_buf_64:ihandle = ion_import_dma_buf_fd(qseecom.ion_clnt, req->ifd_data[i].fd); ... field = (char *) req->cmd_req_buf + req->ifd_data[i].cmd_buf_offset; ... /* Populate the cmd data structure with the phys_addr */ sg_ptr = ion_sg_table(qseecom.ion_clnt, ihandle); ... update_64bit = (uint64_t *) field; *update_64bit = cleanup ? 0 : (uint64_t)sg_dma_address(sg_ptr->sgl);This solves the first issue mentioned above, but not the second one. To let the QSEE kernel know the location of the other ION buffers the trustlet needs to access, it kind of converts the

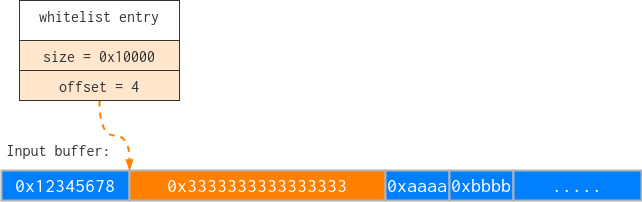

ifd_dataarray from theioctlinto an array of something which in the code is called ansglist_info, but I think a better name for it would be a whitelist entry5.

Each whitelist entry contains the same offset that was in theqseecom_ion_fd_info, but instead of the ION file descriptor it contains the size of the ION buffer. -

Now the QSEE kernel receives the whitelist entries alongside the input/output buffers. When parsing them, for each whitelist entry it goes to the input buffer and reads the address at the specified offset. It then gives the trustlet access to (“whitelists”) the memory from that address and for the size specified in the whitelist entry.

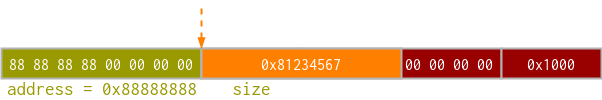

To explain this in a more graphical way, here is how the data in the ioctl would look like:

And this is how the data passed from qseecom to the QSEE kernel would look like:

As you can see, this blends data and metadata. The physical address could have just been “duplicated” inside the whitelist entry alongside the size, but instead we have this more complicated design. Perhaps this was done to save a few bytes?6 Anyway, often where you have over-complicated designs you also have vulnerabilities.

The vulnerability

I have looked into this area of qseecom before and even reported several bugs, but this time I focused on reversing the QSEE side of the communication protocol. This helped me find one more bug and understand its implications.

The bug is that there is no check to make sure addresses of different ION buffers don’t end up overlapping each other. If you do provide qseecom with two ION file descriptors with offsets that cause their addresses to overlap each other, you can cause one whitelist entry to point at a corrupted address which does not belong to any ION buffer; this will get that address whitelisted for the trustlet.

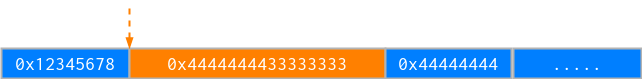

For example, let’s take the diagram from above, but this time add another ION buffer to the ioctl. When qseecom writes the second ION buffer’s address to the input buffer it would look like this:

But when we look at what the first whitelist entry now points to, it would look like this:

(It’s 0x4444444433333333 and not 0x3333333344444444 because it’s little endian)

At this point I realized that if the command I send to the trustlet instructs it to modify memory at the specified address, I can get it to modify memory at that corrupted address. And if the corrupted address happens to contain kernel memory, that could result in privilege escalation.

Avoiding side effects

As can be seen in the diagrams above, there is actually a side effect in what I described. By partially overwriting an address, data around it also gets corrupted. In the diagram you can see that the 0xaaaa and 0xbbbb were overwritten with 0x44444444.

While I could have stuck to only overlapping addresses fully and not partially, I did want more flexibility than that in my exploit.

I realized that I could actually increase the size of the input buffer more than what the trustlet needs, and no error would occur. The trustlet would just read all the data it needs and then ignore the rest. This means that I could perform all the address manipulations at the end of the input buffer, not touching any data that the trustlet is going to read.

This does mean that I would need to know the physical address I want the trustlet to modify beforehand, so I can write it where the trustlet does expect a pointer (instead of letting qseecom do it), but this is also something I am going to solve.

Exploiting the vulnerability

Now that I figured out how to easily trigger the vulnerability without side effects, I sat down to think about what would be the best way to manipulate addresses in order to exploit it. I realized that there is one more detail here which I haven’t really touched yet.

Communicating with pointers: One more detail

Up until now I’ve only discussed how the input buffer can contain pointers to ION buffers that are contiguous in physical memory, but ION buffers can also be non-contiguous, only being contiguous in virtual memory. This usually depends on which heap the ION buffer was allocated from.

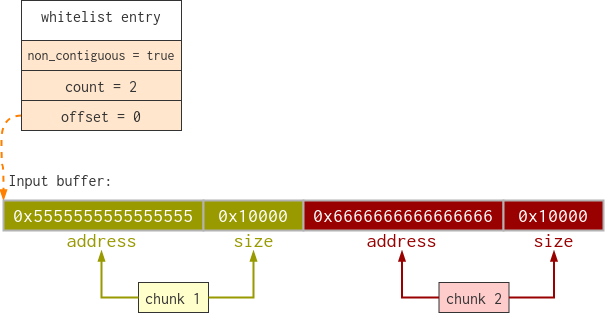

Using non-contiguous ION buffers makes everything more complicated. Instead of writing just a single physical address to the input buffer, qseecom writes a whole array of qseecom_sg_entry_64bit that each contain an address (8 bytes) and a size (4 bytes). This is essentially scatter-gather (sg):

struct qseecom_sg_entry_64bit {

uint64_t phys_addr;

uint32_t len;

} __attribute__ ((packed));

The array is written in qseecom_update_cmd_buf_64:

update_64bit = (struct qseecom_sg_entry_64bit *)field;

for (j = 0; j < sg_ptr->nents; j++) {

update_64bit->phys_addr = cleanup ? 0 :

(uint64_t)sg_dma_address(sg);

update_64bit->len = cleanup ? 0 :

(uint32_t)sg->length;

update_64bit++;

len += sg->length;

sg = sg_next(sg);

}

The whitelist entry of this ION buffer also looks a bit different. A flag is turned on to indicate that this whitelist entry is non-contiguous, and the field which used to be size is now treated as count (the name of the field in the code is actually sizeOrCount). This can all be seen in the following code from qseecom_update_cmd_buf_64, which creates a whitelist entry (this is the code for both contiguous and non-contiguous):

offset = req->ifd_data[i].cmd_buf_offset;

data->sglistinfo_ptr[i].indexAndFlags =

SGLISTINFO_SET_INDEX_FLAG(

(sg_ptr->nents == 1), 1, offset);

data->sglistinfo_ptr[i].sizeOrCount =

(sg_ptr->nents == 1) ?

sg->length : sg_ptr->nents;

To explain it in a more graphical way, here is a diagram of how it would look like:

From the vulnerability point of view, this is very interesting. This allows me to also manipulate the size of a whitelisted buffer, as well as the address.

Whitelisting everything

At this point I stopped to think about my objective here. I know I can get kernel memory whitelisted, but the question is what should I try to whitelist. After thinking for a while I figured: Why not just try to whitelist the whole kernel memory?

One thing that came up useful here is /proc/iomem. This pseudo-file shows what different regions of physical memory are used for. Here’s a snippet from its output:

1b400000-1b7fffff : mnh_pci

1b800000-1bffffff : mnh_pci

80000000-817fffff : System RAM

80080000-803fffff : Kernel code

804a0000-80707fff : Kernel data

88f00000-8aafffff : System RAM

94400000-944fffff : System RAM

95c00000-a10fffff : System RAM

I figured that managing to whitelist all of Kernel code and Kernel data should be enough, even though it’s technically not the whole kernel memory, as it doesn’t include dynamically allocated memory.

One more thing I had to take into account before I started to construct a technique was the limit of 4 ION buffers per request, which means I couldn’t just use as many as I want. More than that, I figured that it would be very useful to have one “normal” ION buffer per request, to allow me to have one pointer to data I fully control, which narrowed me to using only 3 ION buffers in my technique.

At this point I started observing the physical addresses I got for ION buffers I allocated, trying different sizes and different heaps. I found interesting behaviors for the system and the qsecom heaps, which I used in my exploit.

For the system heap I realized that allocating 0x2000 bytes always allocates the two pages as non-contiguous in physical memory. This is enough to get the behavior I described in Communicating with pointers: One more detail.

For the qsecom heap, as I mentioned above, I already knew one behavior, which is that the memory it allocates is always contiguous in physical memory. But I found two more interesting behaviors:

- Memory allocated by this heap is after

Kernel codeandKernel datain physical memory. - Physical addresses of memory allocated by this heap always fit in 32 bits.

This gave me an idea: I could use an address from the qsecom heap to overwrite the size of one of the whitelisted chunks. Since the address fits in 32 bits it would overwrite the size completely (zeroing the following 4 bytes, but that doesn’t really matter). Then if I can zero the address of that chunk completely (or maybe reduce it to a very low number) it means I would whitelist everything from 0 until somewhere after Kernel code and Kernel data.

Now the question I was left with is how to make the address of a chunk become zero.

Spraying ION buffers

I figured that if I manage to get a system ION buffer whose physical addresses all have zeroes as their 4 higher bytes, I could zero their 4 lower bytes using the 4 higher bytes of the qsecom ION buffer, to reach an address that is all zeroes.

To do this I used the fact that some ioctls in qseecom have both a 32 bits and a 64 bits version. For example, I mentioned QSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_MODFD_CMD_64_REQ, but there is also QSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_MODFD_CMD_REQ which is the 32 bits equivalent. I think this is because QSEE supports running both 32 bits and 64 bits trustlets, but to be honest I’m not completely sure.

Anyway, for my exploit I used QSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_MODFD_CMD_REQ. The key here is that for this ioctl there is a check in qseecom to make sure that all physical addresses of ION buffers passed to it fit in 32 bits. If this check fails then the ioctl fails. Since there is really no other reason for the ioctl to fail, I can assume that a failure in this ioctl means that the ION buffer has a physical address that doesn’t fit in 32 bits.

At this point I can kind of “spray” ION buffers, basically continue allocating ION buffers from the system heap and running them through this ioctl. The first one that doesn’t fail fits in 32 bits.

Note that this is the least reliable part of my exploit, because in theory you could just end up allocating more and more ION buffers without ever reaching one that fits in 32 bits. From my experience though, all you really need here is just a bit of patience.

Whitelisting everything: Summary

So I have a technique to whitelist all of the kernel code and data, let’s sum it up:

- Allocate one ION buffer from the

qsecomION heap. Size doesn’t really matter. - Allocate one ION buffer from the

systemION heap. The size should be0x2000which would guarantee two non-contiguous pages in physical memory. - Check if running

QSEECOM_IOCTL_SEND_MODFD_CMD_REQworks for thesystemION buffer. If it doesn’t, allocate another and try again. -

Add the

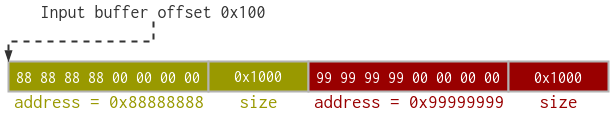

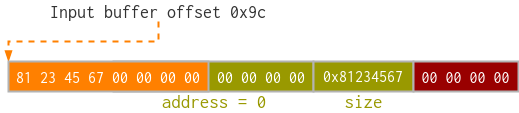

systemION buffer with a far offset (after the data that the trustlet reads), let’s say0x100. At this point the input buffer should look like this:

-

Add the

qsecomION buffer with an offset of0x108so it overwrites the size field of the first entry in the array. So now the input buffer should look like this:

-

Add the same

qsecomION buffer once more, but this time with an offset of0x9cso it zeroes the lower 4 bytes of the address. Now the input buffer should look like this:

- At this point I have all physical memory from 0 until somewhere after kernel code and data whitelisted, which means the trustlet should now be able to access all of the kernel code and data.

Achieving kernel r/w

Granting the trustlet to access all of the kernel code and data is great, but it’s still not enough. I needed to figure out how to make the trustlet perform the modifications I want it to make to the kernel memory.

First thing is of course that I need to know is what physical addresses I want the trustlet to read/write (as mentioned above). This is probably a good time to note that unlike virtual addresses, physical addresses are not randomized. This means that all I have to know is the physical address of a symbol I want to read/write (e.g. the bit that decides if SELinux is enabled) in a certain build, and then I can write it to the input buffer knowing it will always be the same.

So at this point I had one final thing to figure out in order to achieve kernel read/write: Find a command in a trustlet that gives me as much control over data being pointed to in the command, ideally something that copies memory from one place to another. Unfortunately, this turned out to be quite a headache.

I started looking at the possible trustlets I could use, and immediately realized there is one issue here: I was working on Pixel devices, and the thing about Pixel devices is that compared to other vendors they don’t have a lot of trustlets on them. But to be honest, this is actually both bad and good. Of course bad because I don’t have a lot of trustlets to look for a copy functionality in, but good because I can pretty much expect all of the trustlets on a Pixel device to also exist on other devices, which makes my exploit more device-generic.

At this point, it didn’t take me long to narrow my search to the Widevine trustlet. All other trustlets barely have any functionality that deals with pointers, so it was easy to rule them out. Widevine on the other hand is full of functionality; so although it’s very complex, I realized I pretty much had to use it for my exploit.

Reversing Widevine

Widevine is Google’s DRM technology, so this trustlet is basically the parts of Widevine that run on the TrustZone. The problem is that this technology is very complicated, which means that the trustlet is very complicated as well. I also felt that there is not that much documentation available about how it works internally (well, not publicly), which meant I had to just reverse a lot of it.

The issue I kept facing is that even though the trustlet is full of functionality, it was very hard to reach it. Almost all of my commands kept failing due to one check or another before I could reach any interesting functionality. And remember, I wasn’t even trying to do anything malicious at this point, just trying to run valid commands.

The bottom line is that reversing Widevine was quite a challenge in itself, but I’m going to leave it out of the scope of this blog post since I don’t want to make it too long. I did end up learning quite a lot about Widevine, so if you are interested in reversing Widevine yourself let me know; I might publish a separate blog post just about this.

Anyway, after a lot of work reversing Widevine, I found commands that allowed me both to encrypt memory and decrypt memory with the same symmetrical key. This was good enough for me, because if you think about it, encrypt + decrypt (with the same symmetrical key) is just copy with extra steps.

So here are the techniques I came up with to use Widevine in order to perform arbitrary kernel read and arbitrary kernel write, using of course my ability to whitelist the entire kernel code and data. Note that for these techniques I am using the 4th and final ION buffer slot I have in the ioctl (the other three are used to whitelist the whole kernel). I call this buffer the normal ION buffer, because I use this the “normal” way (letting qseecom write its physical address for me).

For arbitrary read:

- Run encrypt while whitelisting the whole kernel. The source address would be whatever physical address I want to read from, while the destination address would be the normal ION buffer.

- Run decrypt in-place on the memory in the normal ION buffer.

- Now the memory in the normal ION buffer should be the memory I wanted to read.

For arbitrary write:

- Write the memory I want to write into the normal ION buffer.

- Run encrypt in-place on the memory in the normal ION buffer.

- Run decrypt while whitelisting the whole kernel. The source address would be the normal ION buffer while the destination address would be the physical address I wanted to write to.

One little caveat regarding the encrypt/decrypt commands is that the size of each operation has to be aligned to the size of an AES block, which is 16 bytes. But this is actually barely an issue. It is not really a problem to read a few bytes more than needed, and if I want to write something that doesn’t align I can always read what was in there beforehand, so when writing I can make sure the extra memory is kept unchanged.

Now was the time to test my arbitrary kernel read/write. I found the physical address of the global variable that decides if SELinux is enabled, changed it to 0 and it worked. I finally had a working exploit :)

Pushing the exploit further

While this was indeed quite satisfying, I figured that since this exploit is super reliable and the primitive of arbitrary physical memory read/write is very powerful, I could push it even further. At this point to make the exploit work I needed to adapt it per build, as I needed to know the physical addresses of the symbols I wanted to modify, and these change per build. I wanted to avoid this part and make my exploit work on different builds and even different devices out of the box.

For this I used kallsyms, which is a mechanism in the Linux kernel that keeps track of all symbols in the kernel and their virtual addresses. This is not a novel idea, Gal Beniamini already used it in one of his blog posts to pretty much do the same thing I wanted to do: Attack the kernel from the TrustZone without knowing any kernel symbols.

The only difference between me and Gal is that he did it when the kernel was still 32 bits, and now it’s 64. The structure of kallsyms changed between the two architectures.

I had to write my own code that uses the arbitrary read in order to scan the kernel memory to find kallsyms, and then parse it (in its ARM64 structure). I did base my code on a tool called vmlinux-to-elf, which analyzes dumped Linux kernels. The tool was made by Marin Moulinier, so thanks Marin :)

But still, my code to find/parse kallsyms is more of a PoC than a robust thing. It worked on the devices I have, but I expect there might be some devices out there it won’t work on.

One issue with kallsyms is that it gives you virtual addresses, not physical. But since it also has a symbol for the virtual base, I could subtract it from any other virtual address I found in order to determine its physical address.

That’s it. At this point my exploit code worked and disabled SELinux on different devices and versions without needing adaptations. I also decided to change the string returned from /proc/version, just to demonstrate that since I have access through physical memory it’s just as easy for me to modify read-only memory as it is to modify read/write memory.

Full exploit summary

Here’s a quick review of all the steps in the exploit:

- Allocate one

qsecomION buffer and onesystemION buffer that has 2 non-contiguous pages in physical memory and whose physical addresses fit in 32 bits. - Setup 3

ifd_dataobjects with theqsecomaddress twice overwriting parts of thesystemwhitelist entry, once to overwrite the size and one to zero the address. We will use theseifd_dataobjects when accessing kernel memory as these whitelist the whole kernel code and data for the trustlet. - Setup the Widevine trustlet to be in a state where we can perform encrypt and decrypt operations.

- Combine encrypt + decrypt with the same symmetrical key to achieve copy, and then combine it with the ability to whitelist the entire kernel from step 2 to get arbitrary kernel read/write.

- Use the arbitrary read to scan physical kernel memory to find the data of kallsyms, then parse it to be able to find the addresses of all symbols.

- Use the addresses we found from kallsyms with the arbitrary write to control whatever we want e.g. disable SELinux.

Source code for the exploit is available on GitHub. Note that although the exploit worked for me on all Qualcomm devices I tried, I of course can’t guarantee it will work on all devices. There could always be unexpected complications, and I still consider it more of a PoC than a robust exploit.

Conclusions

Let’s talk a bit about Android kernel exploitation/mitigation techniques. I haven’t really discussed mitigations yet, and I think it’s actually for a very good reason: At no point have I really encountered a mitigation I needed to bypass when writing this exploit.

The bottom line is that since this exploit deals with physical memory, all kernel mitigations don’t really apply. Addresses are not randomized by ASLR which makes it much simpler to gain full control over kernel memory, and once I do have such control I don’t really care about code execution mitigations such as CFI or stack cookies.

Even thinking about the future, looking into the much-discussed MTE; I haven’t tried but I do believe that such exploit that works on physical memory should also work with MTE enabled, since it’s also a mitigation that only applies in virtual memory.

From an attacker’s point of view, I do think we might see a bit more of a trend to try to exploit components that deal with physical memory, especially if MTE does end up becoming a mainstream kernel mitigation. Also, not having to adapt the exploit per each build is nice to have.

Looking at recent research, I found three other public Android exploits that deal with physical memory:

- CVE-2019-10567 by Guang Gong which exploits a vulnerability around Qualcomm’s Adreno GPU.

- CVE-2020-11179 by Ben Hawkes which exploits the fact that the patch for CVE-2019-10567 was incomplete.

- CVE-2022-20186 by Man Yue Mo which exploits a vulnerability around the Mali GPU. This one is very recent and was published after I finished my research.

From a defender’s point of view, the fact that I was able to exploit the kernel without encountering a single mitigation in the process is a bit concerning. Especially since today the kernel is pretty full of mitigations. I’m also not sure that MTE would have made it any better.

I guess one thing I should say from a defender’s point of view, is that if you haven’t already, make sure to be extra sensitive and take extra care with any component that deals with physical memory.

The last thing I’d like to say here is related to the interesting method of this exploit, attacking the kernel by using the TrustZone. The TrustZone is marketed as a security component, and is supposed to make Android devices more secure. Yet, in this exploit it actually does the opposite, as it created an avenue for me to attack the kernel that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. But I don’t want this blog post to become a rant on how I believe software should be secured, so I’ll leave it at that.

Disclosure and patch

I reported this vulnerability on October 31 2020. It took more than 10 months for it to be patched, as the patch was released on September 2021, both in Qualcomm’s September 2021 Security Bulletin, and in Google’s September 2021 Bulletin. (Yes, it also took me a while to write this blog post)

Qualcomm’s patch for this vulnerability is to add some checks to the qseecom kernel module to make sure addresses of different ION buffer don’t overlap each over. I guess this is pretty much the patch I expected them to have here.

I do think though that the time it took for this patch to be released is a bit concerning. Man Yue Mo recently voiced similar concerns for a vulnerability he reported in the Qualcomm GPU, where he also goes into more details about the patching process. I share his concerns regarding the patching time, and also regarding patch gapping. I also found that the patch for this vulnerability was publicly visible long before it was officially fixed.

So that’s it for the blog post. I hope you found it interesting, and if you have any questions you are always welcome to ping me on Twitter.

-

As far as I understand, at some point Qualcomm actually changed the name to QTEE, where the T represents Trusted. I think it’s a marketing thing? Anyway, I decided to use QSEE in this blog post as that’s the name I’m more used to and also because I feel it makes a bit more sense seeing that the kernel module is still called qseecom. ↩

-

Actually, QSEE technically does operate in virtual addresses, but they are just mirroring the underlying physical memory, so the virtual addresses are the same as the physical ones. This is how the QSEE kernel limits trustlets to only have access to certain memory. ↩

-

I haven’t missed an e there, this is the name, and there is even another ION heap called

qsecom_ta(source). To be honest I’m not quite sure if Qualcomm has some clever reason for omitting one e or if it was just a typo. Personally I’m leaning towards typo :) ↩ -

I am simplifying the process a bit, omitting the fact that this is done through two

ioctls (QSEECOM_IOCTL_SET_MEM_PARAM_REQfirst to save the ION buffer in the kernel) as it’s less relevant. ↩ -

I use this name because the whitelist entries are used in commands such as

QSEOS_CLIENT_SEND_DATA_COMMAND_WHITELISTorQSEOS_TEE_OPEN_SESSION_WHITELIST, but I also think this is a much more indicative name. This is an example of where even though qseecom’s source code is open, some parts of it can be somewhat confusing (what the hell is ansglist_infoused for?), and actually reversing QSEE helped me understand it much better. ↩ -

It’s true that in the case of non-contiguous ION buffers this can in theory save more than just “a few” bytes. I still personally don’t see a huge performance gain here, but maybe I’m wrong? It’s hard for me to tell if this was a design decision made through actual trial and error or if it’s just premature optimization. ↩